1895

Could I but have my dear one back again

From the vastness of the great west unknown,

How would it ease my poor heart's silent pain

As I sit here at even all alone!

That he travels wide makes me more afraid

Who shall his wayward heart and footsteps guide,

For him softer the way my love had made,

So feels my poor heart while he wanders wide.

Cold was the night he left my sanctum warm,

A night of wintry tempest, harsh and wild,

Went forth my dear friend reckless, wild —

I say alone — for who hears angels' feet

As we pass along? Tho' we dream they come,

We hear them not upon the busy street;

We only know a void — we are alone.

Friendship! Thy very name is sorrow's own,

Synonym for parting said for trial,

'Tis I must bear the burden all alone,

And when the tear would start must wear a smile.

— Jessie M. Holland.

Saturday, May 31, 2008

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Flood Time

1895

Across the vale the floods are out,

The floods are out with rush and rout;

Across the world the floods are out,

The land is in the sea,

And round the oak tree that displays

The bronze bright head in wintry days

The roaring current swings and sways,

Shouting his song of glee.

And landsmen now are watermen,

The robin, as the water hen

That makes her nest in reed and fen,

The robin's gone afloat.

The wind that rocks him to and fro

With a soft cradle song and slow

Pleases him in the ebb and flow,

Rocking him in a boat.

Flotsam and jetsam whirling by

The bridge where lovers meet and sigh,

The whirling crows flap wings and cry

And praise themselves that they

Have built their homes one story each,

In the tall masts of elm and beach,

And them no swelling flood can reach

Till all the world be gray.

The westward waters, cool, serene,

Mirror the sunset's gold and green,

A road of flame and emerald sheen

Broken to million lights.

The eastward waters take the moon,

Clad in the pearl from throat to shoon,

Whiter than any lily in June.

She scales the heavenward heights.

— Pall Mall Gazette.

Across the vale the floods are out,

The floods are out with rush and rout;

Across the world the floods are out,

The land is in the sea,

And round the oak tree that displays

The bronze bright head in wintry days

The roaring current swings and sways,

Shouting his song of glee.

And landsmen now are watermen,

The robin, as the water hen

That makes her nest in reed and fen,

The robin's gone afloat.

The wind that rocks him to and fro

With a soft cradle song and slow

Pleases him in the ebb and flow,

Rocking him in a boat.

Flotsam and jetsam whirling by

The bridge where lovers meet and sigh,

The whirling crows flap wings and cry

And praise themselves that they

Have built their homes one story each,

In the tall masts of elm and beach,

And them no swelling flood can reach

Till all the world be gray.

The westward waters, cool, serene,

Mirror the sunset's gold and green,

A road of flame and emerald sheen

Broken to million lights.

The eastward waters take the moon,

Clad in the pearl from throat to shoon,

Whiter than any lily in June.

She scales the heavenward heights.

— Pall Mall Gazette.

Saturday, May 24, 2008

My Choice

1895

What flower shall be mine? Oh, how can I choose

From the myriads that cover the plain?

Shall it be the wild rose that blooms in the wood

Or the buttercup down in the lane?

Fair are the lilies so stately and tall

That grow in the deep meadow grass,

And white are the daisies with bright starry eyes

That greet me whenever I pass.

Forgetmenots, too, so tiny and bright,

Reflecting the blue of the sky,

And cardinal flowers, with scarlet aflame.

Oh, why should I pass them by?

How, how can I choose? Shall it be the wind-flower

That, tremulous, sways in the breeze,

Or the orchid that blooms with a beauty so rare

In the shade of the tall forest trees?

Marsh marigolds grow by the side of the brook,

And here is the white meadow queen,

But I choose the blue violet, modest and sweet,

In its setting of emerald green.

—Vick's Monthly.

What flower shall be mine? Oh, how can I choose

From the myriads that cover the plain?

Shall it be the wild rose that blooms in the wood

Or the buttercup down in the lane?

Fair are the lilies so stately and tall

That grow in the deep meadow grass,

And white are the daisies with bright starry eyes

That greet me whenever I pass.

Forgetmenots, too, so tiny and bright,

Reflecting the blue of the sky,

And cardinal flowers, with scarlet aflame.

Oh, why should I pass them by?

How, how can I choose? Shall it be the wind-flower

That, tremulous, sways in the breeze,

Or the orchid that blooms with a beauty so rare

In the shade of the tall forest trees?

Marsh marigolds grow by the side of the brook,

And here is the white meadow queen,

But I choose the blue violet, modest and sweet,

In its setting of emerald green.

—Vick's Monthly.

Sunday, May 18, 2008

They Were Just Too Mean

1895

This Was the Trouble About Jim and Myra and the Gloomy Girl In Red.

"The world is hollow," remarked the girl in red.

"It is," gloomily assented the girl whose new gown does not fit, "but I don't see how you ever found it out."

"By accident, dear. It happened the day after the cards were sent out. I had a note from Dan saying that he must see me once more before I was Jim's wife. Of course I didn't really care for Dan, but it is soothing to one's vanity to know that the best man is dying of envy of the bridegroom, who has no idea of it."

"So you said you would see him?"

"I did. I felt that it would do Jim no harm if Dan did tell me once more that life was a blank without me, and it was really my last chance too. Still I didn't dare to let him come to the house."

"But where else could you see him?"

"At Myra's. She is to be maid of honor, you know, and Jim used to be quite devoted to her, so I knew she'd never dare to tell on me lest people would think her jealous."

"When I want advice, I shall know where to come for it."

"Very well, do. Well, I didn't send her word that I was coming, for I didn't want anything down on paper. As luck would have it, just as I was starting Jim sent up a box of roses and a melancholy note saying that a business engagement he couldn't shirk would prevent him from coming up that evening."

"You were in luck."

"So I thought. Well, I just throw myself on Myra's mercy. She wasn't a bit pleased, as I could see, but she submitted with the best grace she could. She said she would keep everybody out of the library so we could have a long, quiet evening, and not to worry about her, as she would probably have company."

"That was nice of her."

"Oh, very nice. Dan came early, and we had a perfectly lovely time. He begged me to elope the day before the wedding, recited two poems about his despair and hinted at suicide. Oh, it was splendid! I cried myself almost to a jelly. At about half past 10 I really couldn't stand it any longer, so I told Dan that we must go in and speak to Myra, for the front parlor was so quiet that her caller had evidently failed to come. So, after another eternal farewell, we went in."

"Well?"

"It wasn't well — it was ill! Myra's caller was there. He was Jim. He was holding her hand and bidding her goodby forever! Oh, was ever a poor girl so cruelly deceived as I?" — Chicago Tribune.

This Was the Trouble About Jim and Myra and the Gloomy Girl In Red.

"The world is hollow," remarked the girl in red.

"It is," gloomily assented the girl whose new gown does not fit, "but I don't see how you ever found it out."

"By accident, dear. It happened the day after the cards were sent out. I had a note from Dan saying that he must see me once more before I was Jim's wife. Of course I didn't really care for Dan, but it is soothing to one's vanity to know that the best man is dying of envy of the bridegroom, who has no idea of it."

"So you said you would see him?"

"I did. I felt that it would do Jim no harm if Dan did tell me once more that life was a blank without me, and it was really my last chance too. Still I didn't dare to let him come to the house."

"But where else could you see him?"

"At Myra's. She is to be maid of honor, you know, and Jim used to be quite devoted to her, so I knew she'd never dare to tell on me lest people would think her jealous."

"When I want advice, I shall know where to come for it."

"Very well, do. Well, I didn't send her word that I was coming, for I didn't want anything down on paper. As luck would have it, just as I was starting Jim sent up a box of roses and a melancholy note saying that a business engagement he couldn't shirk would prevent him from coming up that evening."

"You were in luck."

"So I thought. Well, I just throw myself on Myra's mercy. She wasn't a bit pleased, as I could see, but she submitted with the best grace she could. She said she would keep everybody out of the library so we could have a long, quiet evening, and not to worry about her, as she would probably have company."

"That was nice of her."

"Oh, very nice. Dan came early, and we had a perfectly lovely time. He begged me to elope the day before the wedding, recited two poems about his despair and hinted at suicide. Oh, it was splendid! I cried myself almost to a jelly. At about half past 10 I really couldn't stand it any longer, so I told Dan that we must go in and speak to Myra, for the front parlor was so quiet that her caller had evidently failed to come. So, after another eternal farewell, we went in."

"Well?"

"It wasn't well — it was ill! Myra's caller was there. He was Jim. He was holding her hand and bidding her goodby forever! Oh, was ever a poor girl so cruelly deceived as I?" — Chicago Tribune.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

A Story Called "Plagiarized" (1895)

1895

Plagiarized

The young couple stood on the bank opposite the Gadfly contemplating that small boathouse with something less than a feeling of ownership than they had hitherto experienced. A fiery little steamer went up the river, and the waves, taking advantage of the confusion, ran and kissed the green bank and were off again before the green bank had time to protest. From the top deck of the Gadfly came a song to the ears of Mr. Stewart of Throgmorton street, and of young Mrs. Stewart, that they were beginning to know quite well, albeit Miss Bagge, the singer, had only been there since the morning. Miss Bagge accompanied herself on the banjo and accompanied herself all wrong:

"I'm a little Alabarmer coon;

A'nt been born very long."

"I wonder," said little Mrs. Stewart — "I wonder, now, how many more times she's going to play that?"

"My dear love," said Mr. Stewart, sitting down on the bank.

"Don't call me your dear love, Henry, until that dreadful girl is gone."

"My dear Mrs. Stewart, what can I do? I can't treat her as we brokers treat a stranger who happens to stroll into the house, can I? You wouldn't care for me to catch hold of her and mash her hat in and hustle her out of the place."

"I shouldn't. All you have to do is to be distant with her."

"One can't be very distant on a small houseboat."

"I believe you like Miss Bagge still," said Mrs. Stewart.

"I don't mind her when she's still," said Mr. Stewart. "It's when she bobs about and plays that da"—

"Henry, dear!"

—"plays that banjo of hers that she makes me hot."

The shrill voice came across the stream:

"Hush-a-by, don't you cry, mammy's little darling.

Papa's gwine to smack you if you do."

"Boat ahoy!" called Stewart.

The boy on the Gadfly came up from somewhere and pulled over to them and conveyed them to the houseboat. Miss Bagge, looking down from between the Chinese lanterns, gave a little shriek of delight as their boat bumped at the side of the Gadfly.

"Oh, you newly married people!" she cried archly as she bunched up her skirts and came skittishly down the steps. "Where have you been? Leaving poor little me alone with my music for such a time!"

"Did you say music, Miss Bagge?"

"Yes, dear Mrs. Stewart. My banjo, you know."

"Oh!" said little Mrs. Stewart.

"Afraid you don't like plantation melodies, Mrs. Stewart."

"I used to think I did, Miss Bagge."

Stewart had gone along to get something iced to drink and something in the shape of cigar to smoke.

"How things change, Mrs. Stewart, don't they? I'm sure it doesn't seem six years ago — hem — Mr. Stewart and I and ma and two or three others came up to Marlow. I think that was long before your day, before you came over from Melbourne, and we did really have the most exquisite time."

"Have you looked through the evening paper, Miss Bagge?" interrupted little Mrs. Stewart hurriedly.

"Oh, yes, dear; I've looked through it twice. One or two most interesting cases."

"Where did you put it? I want to see what O'Brien has done for Middlesex."

"I've dropped it somewhere," said Miss Bagge. "Could the boy go up for my trunk before it gets dark? I left it at the station, and I shall have some more things down next week."

"Next week!"

Miss Bagge put her hand to her brown thin neck and gave a cough of half apology.

"If I stay longer, I shall have to run up to town one day to do some shopping."

There was a pause. The rings of smoke from Stewart's cigar at the other end of the boat floated down by them. The boy below broke a few plates and danced a few steps of a breakdown to cover the noise.

"Dear Henry! How the scent of his cigar does remind me of old times! I remember so well that night at Marlow" —

"Miss Bagge, will you go and play something?"

Miss Bagge went obediently and strummed her banjo and mentioned once more that she was a little Alabama coon, and young Mrs. Stewart ran hurriedly to her husband.

"I'm going to quarrel with her," she said breathlessly.

"That's right," said Henry calmly. "Anything to stop that row."

"I'm going to ask her to go back to town tonight, Henry."

"But, my dear, isn't that rather rude?"

"Of course it is. That's why I am doing it. You'll have to see her to the station."

The private row was quickly and quietly over. When the last word had been spoken, the self invited guest begged ten minutes to write a letter, and then she pronounced herself ready for Stewart's escort to the station. "Sorry you are obliged to go, Miss Bagge," said Stewart politely.

"It's an important engagement," said Miss Bagge, trembling, "or I should have staid. Goodby, dear Mrs. Stewart. I dare say we shall meet again soon."

Now an odd thing happened. As Stewart handed his charge into the boat a letter fell from her pocket on the deck of the Gadfly. Mrs. Stewart, in her usual good temper, now that her husband's old admirer was departing, called to her as soon as she noticed the letter, but Miss Bagge paid no attention. It almost seemed that she did not want to hear. When Mrs. Stewart picked it up and saw that it was addressed to Henry Stewart, Esq., and marked "Private and confidential," she opened it without a moment's hesitation:

MY DEAREST HENRY — It is so sweet to be near you again. Just as the wind sighs for the seashore, so do I sigh for you. Can you imagine what you are and ever have been to me? You are indeed my king, and you know I am your willing slave. Yours faithfully, CONSTANCE BAGGE.

Young Mrs. Stewart sank down on a low deck chair and gasped and looked across at the two.

"Well," she said, "now this is fearful."

There would be a good half hour before Henry returned, and in that good half hour it was necessary to decide what was to be done. What was quite clear was that the creature must have had some encouragement to induce her to write such a letter, and —

"Why, she is taking his arm!" she cried.

Indeed, Miss Constance Bagge was resting her hand on the arm of Mrs. Stewart's husband. Henry was carrying her banjo, and, looking back, laughingly waved it at his wife.

"Does this mean," asked Mrs. Stewart distractedly, "that they will never come back?"

The letter seemed to explain his slight difference in agreeing to the lady's dismissal. It explained also why when Miss Bagge had that morning made her unexpected appearance on the bank, hailing the boy with a shrill "Hi!" Henry had only laughed very much.

Mrs. Stewart summoned the boy.

"Yes, mem, there is a trine up liter than this. It leaves Thames Ditton at 11:15, and you got to good old Waterloo at about ten to 12. And I wish to Gawd," added the boy piously, "that I was there nah. This plice is a lump too quiet for me."

That would give half an hour to speak her mind to Henry (if he did come back) just half an hour to extract from him a confession and then rush for the last train up. At Waterloo she could take a cab to Uncle George's, and if Uncle George couldn't see her through, why, nobody could. Uncle George was an agent general. He was a stern man and treated everybody as severely as though they were his fellow countrymen.

The white flanneled figure came back to the riverside.

"He has managed to say goodby, then," said Mrs. Stewart fiercely. "I should like to have seen the parting."

Henry came on board and went straight to her, and, with the assurance of new husbands, kissed her neck.

"She's an impossible creature," said Stewart. He sat down beside his wife and took an evening paper from his pocket. "I believe she took the extra away with her. I've had to buy another."

There was something in little Mrs. Stewart's throat that prevented her for the moment from starting her lecture.

"She wasn't so bad, you know," he went on, "in the old days. Of course I was a mere youth then. But now she's too terrible for words. I suppose if girls don't get married they get warped and changed."

"I want to speak to you, Henry," she said steadily.

"Oh, bother that boy!" he exclaimed. "We must get rid of him, dear. He's a nuisance."

"It wasn't about the boy."

"Not the boy? Well, then —. Hello! Here's a funny case."

She went on very quietly:

"I want to speak to you seriously, Henry, about a matter that has, by accident, come to my notice. I don't want to seem to bother too much about it, and I suppose if I were as free as some women are I shouldn't mind it in the least. But my mind is quite made up."

He was not listening, but her head was averted, and she went on.

"I have left the keys in the bedroom, and my account book is totaled up to date, with the exception of the bill that came in today. There is no reason why we should have any high words."

"I beg your pardon, dear. I haven't heard a word that you were saying."

He had found the news page in the evening paper and was reading with much interest a diverting breach of promise case.

"I was only saying" — she raised her voice to a pitch of distinctness — "that" —

"Look here; here's an idiotic letter the girl writes to the fellow."

"I don't want to hear it, thank you."

"Yes, you do. Listen, this is how it goes: 'Just as the wind sighs for the seashore, so do I sigh for you.' Why, the wind doesn't sigh for the seashore, does it?"

"Go on, please," she said quickly. "Read the rest of the letter. Is it really in the paper, Henry?"

"Look for yourself, dear. It's too funny for words. 'So do I sigh for you. Can you imagine what you are and over have been to me? You are indeed my king, and you know that I am your willing slave.' "

"Why," cried Mrs. Stewart, "that's word for word the same."

"As what?"

"It doesn't matter, dear."

She took from her blouse the letter that the disappointed Miss Bagge, with deplorable lack of originality, had copied from the evening paper.

"Don't people do some silly things, Winifred, dear, when they are in love?"

She took a marguerite from the bowl on the table and stuck it in her hair. Then she tore up the letter and gave the pieces a little puff to send them out on the stream.

"I b'lieve you," said Mrs. Stewart.

"Shall you want to be rowed across for that last trine, mem?" demanded the boy, putting his head out of a window, "or is the guv'nor going to do it?"

"The last train?" echoed Mrs. Stewart. "Why, of course not, James. Go to bed at once."

"That boy's quite mad," said Stewart, turning over a page of the paper to find the cricket. "We must get rid of him." — St. James Budget.

Plagiarized

The young couple stood on the bank opposite the Gadfly contemplating that small boathouse with something less than a feeling of ownership than they had hitherto experienced. A fiery little steamer went up the river, and the waves, taking advantage of the confusion, ran and kissed the green bank and were off again before the green bank had time to protest. From the top deck of the Gadfly came a song to the ears of Mr. Stewart of Throgmorton street, and of young Mrs. Stewart, that they were beginning to know quite well, albeit Miss Bagge, the singer, had only been there since the morning. Miss Bagge accompanied herself on the banjo and accompanied herself all wrong:

"I'm a little Alabarmer coon;

A'nt been born very long."

"I wonder," said little Mrs. Stewart — "I wonder, now, how many more times she's going to play that?"

"My dear love," said Mr. Stewart, sitting down on the bank.

"Don't call me your dear love, Henry, until that dreadful girl is gone."

"My dear Mrs. Stewart, what can I do? I can't treat her as we brokers treat a stranger who happens to stroll into the house, can I? You wouldn't care for me to catch hold of her and mash her hat in and hustle her out of the place."

"I shouldn't. All you have to do is to be distant with her."

"One can't be very distant on a small houseboat."

"I believe you like Miss Bagge still," said Mrs. Stewart.

"I don't mind her when she's still," said Mr. Stewart. "It's when she bobs about and plays that da"—

"Henry, dear!"

—"plays that banjo of hers that she makes me hot."

The shrill voice came across the stream:

"Hush-a-by, don't you cry, mammy's little darling.

Papa's gwine to smack you if you do."

"Boat ahoy!" called Stewart.

The boy on the Gadfly came up from somewhere and pulled over to them and conveyed them to the houseboat. Miss Bagge, looking down from between the Chinese lanterns, gave a little shriek of delight as their boat bumped at the side of the Gadfly.

"Oh, you newly married people!" she cried archly as she bunched up her skirts and came skittishly down the steps. "Where have you been? Leaving poor little me alone with my music for such a time!"

"Did you say music, Miss Bagge?"

"Yes, dear Mrs. Stewart. My banjo, you know."

"Oh!" said little Mrs. Stewart.

"Afraid you don't like plantation melodies, Mrs. Stewart."

"I used to think I did, Miss Bagge."

Stewart had gone along to get something iced to drink and something in the shape of cigar to smoke.

"How things change, Mrs. Stewart, don't they? I'm sure it doesn't seem six years ago — hem — Mr. Stewart and I and ma and two or three others came up to Marlow. I think that was long before your day, before you came over from Melbourne, and we did really have the most exquisite time."

"Have you looked through the evening paper, Miss Bagge?" interrupted little Mrs. Stewart hurriedly.

"Oh, yes, dear; I've looked through it twice. One or two most interesting cases."

"Where did you put it? I want to see what O'Brien has done for Middlesex."

"I've dropped it somewhere," said Miss Bagge. "Could the boy go up for my trunk before it gets dark? I left it at the station, and I shall have some more things down next week."

"Next week!"

Miss Bagge put her hand to her brown thin neck and gave a cough of half apology.

"If I stay longer, I shall have to run up to town one day to do some shopping."

There was a pause. The rings of smoke from Stewart's cigar at the other end of the boat floated down by them. The boy below broke a few plates and danced a few steps of a breakdown to cover the noise.

"Dear Henry! How the scent of his cigar does remind me of old times! I remember so well that night at Marlow" —

"Miss Bagge, will you go and play something?"

Miss Bagge went obediently and strummed her banjo and mentioned once more that she was a little Alabama coon, and young Mrs. Stewart ran hurriedly to her husband.

"I'm going to quarrel with her," she said breathlessly.

"That's right," said Henry calmly. "Anything to stop that row."

"I'm going to ask her to go back to town tonight, Henry."

"But, my dear, isn't that rather rude?"

"Of course it is. That's why I am doing it. You'll have to see her to the station."

The private row was quickly and quietly over. When the last word had been spoken, the self invited guest begged ten minutes to write a letter, and then she pronounced herself ready for Stewart's escort to the station. "Sorry you are obliged to go, Miss Bagge," said Stewart politely.

"It's an important engagement," said Miss Bagge, trembling, "or I should have staid. Goodby, dear Mrs. Stewart. I dare say we shall meet again soon."

Now an odd thing happened. As Stewart handed his charge into the boat a letter fell from her pocket on the deck of the Gadfly. Mrs. Stewart, in her usual good temper, now that her husband's old admirer was departing, called to her as soon as she noticed the letter, but Miss Bagge paid no attention. It almost seemed that she did not want to hear. When Mrs. Stewart picked it up and saw that it was addressed to Henry Stewart, Esq., and marked "Private and confidential," she opened it without a moment's hesitation:

MY DEAREST HENRY — It is so sweet to be near you again. Just as the wind sighs for the seashore, so do I sigh for you. Can you imagine what you are and ever have been to me? You are indeed my king, and you know I am your willing slave. Yours faithfully, CONSTANCE BAGGE.

Young Mrs. Stewart sank down on a low deck chair and gasped and looked across at the two.

"Well," she said, "now this is fearful."

There would be a good half hour before Henry returned, and in that good half hour it was necessary to decide what was to be done. What was quite clear was that the creature must have had some encouragement to induce her to write such a letter, and —

"Why, she is taking his arm!" she cried.

Indeed, Miss Constance Bagge was resting her hand on the arm of Mrs. Stewart's husband. Henry was carrying her banjo, and, looking back, laughingly waved it at his wife.

"Does this mean," asked Mrs. Stewart distractedly, "that they will never come back?"

The letter seemed to explain his slight difference in agreeing to the lady's dismissal. It explained also why when Miss Bagge had that morning made her unexpected appearance on the bank, hailing the boy with a shrill "Hi!" Henry had only laughed very much.

Mrs. Stewart summoned the boy.

"Yes, mem, there is a trine up liter than this. It leaves Thames Ditton at 11:15, and you got to good old Waterloo at about ten to 12. And I wish to Gawd," added the boy piously, "that I was there nah. This plice is a lump too quiet for me."

That would give half an hour to speak her mind to Henry (if he did come back) just half an hour to extract from him a confession and then rush for the last train up. At Waterloo she could take a cab to Uncle George's, and if Uncle George couldn't see her through, why, nobody could. Uncle George was an agent general. He was a stern man and treated everybody as severely as though they were his fellow countrymen.

The white flanneled figure came back to the riverside.

"He has managed to say goodby, then," said Mrs. Stewart fiercely. "I should like to have seen the parting."

Henry came on board and went straight to her, and, with the assurance of new husbands, kissed her neck.

"She's an impossible creature," said Stewart. He sat down beside his wife and took an evening paper from his pocket. "I believe she took the extra away with her. I've had to buy another."

There was something in little Mrs. Stewart's throat that prevented her for the moment from starting her lecture.

"She wasn't so bad, you know," he went on, "in the old days. Of course I was a mere youth then. But now she's too terrible for words. I suppose if girls don't get married they get warped and changed."

"I want to speak to you, Henry," she said steadily.

"Oh, bother that boy!" he exclaimed. "We must get rid of him, dear. He's a nuisance."

"It wasn't about the boy."

"Not the boy? Well, then —. Hello! Here's a funny case."

She went on very quietly:

"I want to speak to you seriously, Henry, about a matter that has, by accident, come to my notice. I don't want to seem to bother too much about it, and I suppose if I were as free as some women are I shouldn't mind it in the least. But my mind is quite made up."

He was not listening, but her head was averted, and she went on.

"I have left the keys in the bedroom, and my account book is totaled up to date, with the exception of the bill that came in today. There is no reason why we should have any high words."

"I beg your pardon, dear. I haven't heard a word that you were saying."

He had found the news page in the evening paper and was reading with much interest a diverting breach of promise case.

"I was only saying" — she raised her voice to a pitch of distinctness — "that" —

"Look here; here's an idiotic letter the girl writes to the fellow."

"I don't want to hear it, thank you."

"Yes, you do. Listen, this is how it goes: 'Just as the wind sighs for the seashore, so do I sigh for you.' Why, the wind doesn't sigh for the seashore, does it?"

"Go on, please," she said quickly. "Read the rest of the letter. Is it really in the paper, Henry?"

"Look for yourself, dear. It's too funny for words. 'So do I sigh for you. Can you imagine what you are and over have been to me? You are indeed my king, and you know that I am your willing slave.' "

"Why," cried Mrs. Stewart, "that's word for word the same."

"As what?"

"It doesn't matter, dear."

She took from her blouse the letter that the disappointed Miss Bagge, with deplorable lack of originality, had copied from the evening paper.

"Don't people do some silly things, Winifred, dear, when they are in love?"

She took a marguerite from the bowl on the table and stuck it in her hair. Then she tore up the letter and gave the pieces a little puff to send them out on the stream.

"I b'lieve you," said Mrs. Stewart.

"Shall you want to be rowed across for that last trine, mem?" demanded the boy, putting his head out of a window, "or is the guv'nor going to do it?"

"The last train?" echoed Mrs. Stewart. "Why, of course not, James. Go to bed at once."

"That boy's quite mad," said Stewart, turning over a page of the paper to find the cricket. "We must get rid of him." — St. James Budget.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

The Little Girl Who Would n't Say Please

1875

1875BY M. S. P.

THERE was once a small child who would never say please,

I believe, if you even went down on your knees.

But, her arms on the table, would sit at her ease,

And call out to her mother in words such as these:

"I want some potatoes!" "Give me some peas!"

"Hand me the butter!" "Cut me some cheese!"

So the fairies, this very rude daughter to tease,

Once blew her away in a powerful breeze,

Over the mountains, and over the seas,

To a valley where never a dinner she sees,

But down with the ants, the wasps, and the bees,

In the woods she must live till she learns to say please.

—St. Nicholas, June 1875, p. 471.

Note: I left "Would n't" as it originally was printed, except the whole title was capitalized.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

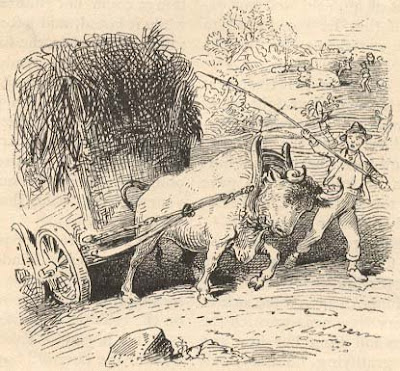

Boy and Ox

1875

1875(Translated from the German of W. HEY by THEODORE FAY.)

"GOOD-DAY, Mr. Ox! Of what do you think?

In deep scientific reflection you sink."

"Thanks, thanks!" the ox answered, as chewing he sat;

"You do me much honor! I 'm not wise as that.

To men I leave science and study and thinking;

My business is pulling and eating and drinking.

They may toil to distinguish the false from the true;

But I am contented to sit here and chew."

He had not chewed long when his good master spoke:

"Ho! the ox to the wagon. Quick! on with the yoke."

The wagon was heavily loaded that day;

The ox bent his forehead and pulled it away.

Had great thinkers been called to drag up the hill

That wagon, 't would surely be standing there still!

—St. Nicholas, June 1875, p. 468.

My First Trout

1875

1875BY EDWARD W. CADY.

Did you ever catch a trout? It is very exciting sport, especially the first time.

There are two kinds of trout, brook-trout and lake-trout. The name indicates where they are found; but the lake-trout is very much larger, and not nearly so handsome as the other. The brook-trout varies in size from about as long as your hand to a foot or more, and is of a reddish-gray color and beautifully marked with red and yellow spots. He is classed among the "game" fish, because trout-fishing requires skill in the fisherman, and is considered excellent sport. Trout are considered delicious eating, too. A brook-trout which weighs about a pound is considered a fair-sized fish, and one that weighs five pounds, a monster; but this last is not very common.

The water where trout live is very clear and cold, and they generally prefer a shady pool or the foot of a little cascade. Woe to the grasshopper which happens to jump into the water there, or the innocent butterfly hovering too near the surface!

The trout never hesitates to jump clear out of the water to catch a bug flying near the surface. If you chanced to be close by at the time, you would be startled by a rush and a plunge, just like a flash of lightning, and good-bye to Mr. Grasshopper or Miss Butterfly!

It does n't seem to make any difference to the trout how small a brook is. I remember a little brook so narrow that the grass growing over concealed it from sight, and it seemed just as though you were fishing in the grass. This stream ran across a field where there were no trees nor bushes, and it seemed very queer to walk out into the middle of the field, let your line down through the grass, and pull trout right out of it.

But I began to tell you how I caught my first trout. It was one Summer when I was about ten years old. I used to go to my grandfather's in Massachusetts every Summer, and spend most of the time fishing, for I was very fond of it. I soon acquired a great reputation as a young fisherman, and felt very proud when I came home along the main street of the town with a large fish. But when I did n't catch any, it was always pleasantest to come through the fields by the back way.

The fish I caught were pickerel, perch, and shiners. I had never caught a trout. I had read about them, however, in a book on fishing which I owned — how shy they were, and how much skill it required to throw a fly well.

Do you know what "throwing a fly" means? If you don't, the book on fishing will explain it to you. You will read, as I did, all about the different kinds of flies, and what kind of a fly the trout likes this month and what kind that. For you must know that at different seasons the trout changes his diet just as we do; and just as in Spring we are very fond of lamb and green peas, so Mr. Trout must have a big brown bug with red head or white tail, or any jolly bug which is in the season. There are workmen who make artificial flies, which look so natural, that sometimes you yourselves may be deceived by them as well as the trout.

On this particular Summer which I am speaking about, my uncle had made me a present of a trout-pole, and, although I had not expected to use it, for it was too slender for the fish I was in the habit of catching, I had brought it with me to the country, so as to have it ready at any time.

Now, there was not much trout-fishing in the neighborhood where my grandfather lived. In fact, no one knew where there was any trout except one old man, the landlord of the tavern. He would take his horse and wagon, drive off before daylight, and come home with a fine string of fish. He never would tell any one where he went. I went one day and said to him, confidentially:

"Mr. Dickey, I want to catch some trout. Can you tell me where to go?"

"Why," he said, "go up along Bull brook, and you 'll find some."

I knew, by the way he said it, that he was n't telling me where he went. Still, I made up my mind I would go to Bull brook and try there. Bull brook was about three miles from the village, with not a single house for miles around. It was a lonely place, full of thickets, and was called Bull brook because a great many cattle were pastured about there.

Early in the morning, I started off with my pole, which being jointed could be carried very conveniently. I trudged along the road, which kept winding and growing more and more lonely and dismal, on account of large beech-trees and poplars and gloomy-looking pines which grew along the side of the road, and almost shut out the sunlight. I felt a little afraid of meeting a cross bull, but I whistled a lively tune, and marched on bravely.

At last I arrived at the brook, and got over the stone wall at the side of the road. There was a thick growth of bushes along the edge of the stream, so that I had to walk some distance before I found an opening where I could get close to the water. Everything was so still that I felt rather nervous and almost expected to see a fierce bull rush out upon me from somewhere. Crickets were chirping, and different kinds of insects were buzzing and humming. No other sound. But hark! What was that? A splash in the brook.

A bull-frog, thought I. I looked in to see if I could discover him. There he was in the bottom of the shallow brook. No, on closer inspection that was not a bull-frog. It could n't be a fish, for fish swim around, and this little dark thing, whatever it was, was lying quite still on the bottom.

Just then, while I was wondering what it was, a grasshopper, which had jumped by mistake into the middle of the brook, went kicking along on the top of the water. In an instant there was a gleam just where the grasshopper was swimming, and before you could say "Jack Robinson" the grasshopper was gone. I was no longer in doubt about the queer thing at the bottom of the brook. It had disappeared. I knew it must be a trout.

"Ah!" said I to myself, "I 'll catch you, Mr. Trout! Then wont the folks in town be surprised, and wont they want to know where I caught him!"

I actually believe I thought more at that moment of what the people would say than I did of catching the trout. I was quite excited. I trembled all over. I captured a grasshopper, and my hand shook while I was putting it on the little hook. I got behind a bush and very carefully lowered my line until the bait touched the surface of the water.

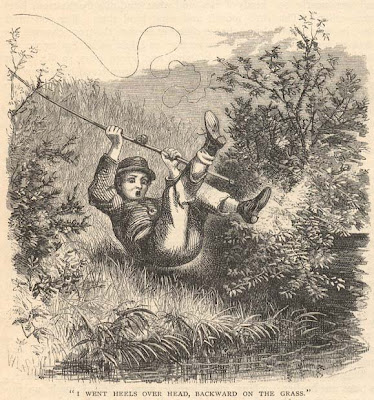

I was terribly excited, as much so as if the brook was a big cannon and the moment the bait touched it there would be a tremendous explosion. There was an explosion, but of a different sort. A plunge, a splash, and I gave a jerk strong enough to tear the bottom of the brook right out.

I went heels over head backward on the grass, and, on scrambling to my feet, looked eagerly at the end of the line to see my trout. But no trout was there, and what was more, the grasshopper was gone.

"What a fool I was," said I to myself, "to tear the line out of the water in that way, and scare all the fish. Now I wont catch any, and the people will laugh at me when I get home."

I caught another grasshopper, and tried again and again, but it was of no use. The fish were evidently frightened. My feelings, from the highest pitch of hope and exultation, were reduced to those of despair and chagrin. I almost cried. I hated to give it up; so I tried a little further down the brook.

This time the grasshopper lay undisturbed on the top of the water for several minutes, and I was just about to pull him up and try somewhere else, when there was a ripple in the water — a splash! The grasshopper disappeared, and there was a jerk on my line! I, too, gave a jerk upward. Oh, how delightfully hard the line pulled up! And then, as I whisked my pole round toward the land, there came out the water a silvery, sparkling fish! In a moment, he was lying on the grass — my first trout!

How I walked around him and gazed at him, and admired his beautiful spots, resplendent in the sun!

No more fishing that day. I had my fish. It only remained now to get home. It was the middle of the afternoon when I folded up my rod, and with my trout strung upon a piece of fish-line, started homeward. I went along the road pretty rapidly, I can tell you. I had no fear of bulls now. I was too much interested in getting home with my fish to think about that. I verily believe if I had met a bull, and he had tossed me, I should have gone up into the air holding on to that trout like a martyr. Alexander the Great, when he entered in a triumphal car one of the cities he had conquered, could not have felt prouder than I did when I entered the village, dusty and tired, and exhibited my prize to the astonished townspeople.

I have a great many times in my life worked hard and overcome difficulties, but I do not remember ever feeling such satisfaction and such pride as when I caught my first trout.

—St. Nicholas, June 1875, pp. 459-461.

Note: I left the contractions the way they were, "wont" and the others with a space, except the halves of "don't" were closer together.

Milmy-Melmy

MILMY-MELMY

By RACHEL POMEROY.

MANY hundred years ago,

People say,

Lived in busy Rhineland

Giants gay;

Folks of mighty stature,

Made so tall,

They would hit the sky in walking —

Stars and all.

When one stretched him on a mount

For a nap,

Why, the clouds would fit him

Like a cap;

In the valley under

Sprawled his toes;

How he could get out of bed

No one knows!

Did he snore a little loudish

(Do you wonder)?

People only thought it

Heavy thunder.

Did he have the nightmare,

Knock-a-knock!

Everybody grimly muttered:

"Earthquake shock!"

One of these tremendous fellows,

I suppose,

Could have hung your father

On his nose.

Half a score like you, sir,

(Don't look pale!)

Might have straddled see-saw

His thumb-nail.

He'd have been a crony

Worth the knowing!

For they were the kindest

Creatures going.

So good-natured, somehow,

In their ways;

Not a bit like naughty giants

Now-a-days.

Well, the biggest one among 'em,

So they tell me,

Had a pretty daughter —

Milmy-Melmy;

Ten years old precisely —

To a T;

Stout enough to make a meal of

You and me.

On her birthday, Milmy-Melmy,

All alone,

Started on a ramble —

Unbeknown.

Left her toys behind her

For a run; —

Big as elephants and camels,

Every one.

Through the country, hill and valley,

Went she fast;

Willows bent to watch her

As she passed;

Hemlock slender, poplar

Straight and high,

Brushed their tops against her fingers,

Tripping by.

Half a mile to every minute —

Like enough,

Though she found the going

Rather rough;

Men folk, glancing at her,

Cried aloud:

"We shall have a shower shortly —

See the cloud!"

Milmy-Melmy thought it rather

Jolly play

Nurse to leave behind, and

Run away;

In her life (imagine

If you can)

She had never seen a woman,

Or a man.

Three times thirty leagues of trudging

(Listen now)

Brought her to a plowman

At his plow;

Getting rather tired,

Stubbed her toe;

Stooped to see what sort of pebble

Hurt her so.

Picking up the plow and plowman,

Oxen, too,

Milmy-Melmy stared at

Something new!

Stuck them in her girdle,

Clapped her hands

Till the mountain echoes answered

Through the lands.

"Here's a better birthday present,"

Shouted she,

"Than the leather dollies

Made for me.

These are living playthings —

Very queer;

La! the cunning little carriage —

What a dear!"

So into her apron, tying

The new toy,

Off she hurried homeward

Full of joy;

Stood it on a table

In the hall;

Ran to bring her father to it,

Told him all.

"Milmy-Melmy," cried the giant,

"What a shame!

You must take the plaything

Whence it came.

These are useful workers,

Daughter mine,

Getting food for human beings, —

Corn and wine.

"Never meddle with such tiny

Folks again;

Only ugly giants love to

Trouble men."

Milmy-Melmy pouted

('T was n't nice),

But she carried back the playthings

In a trice.

When she 'd made her second journey,

Little sinner

Really felt too tired

For her dinner

So to bed they put her,

Right away,

And she had her birthday pudding

The next day.

What the plowman did about it,

Mercy knows!

Must have thought it funny,

I suppose.

If you want a moral,

Ask a fly

What he thinks of giants such as

You and I!

—St. Nicholas, June 1875, pp. 457-458.

Note: Each second line should be indented approximately 2 em spaces. Left quote marks were hanging outside the left margin.

By RACHEL POMEROY.

MANY hundred years ago,

People say,

Lived in busy Rhineland

Giants gay;

Folks of mighty stature,

Made so tall,

They would hit the sky in walking —

Stars and all.

When one stretched him on a mount

For a nap,

Why, the clouds would fit him

Like a cap;

In the valley under

Sprawled his toes;

How he could get out of bed

No one knows!

Did he snore a little loudish

(Do you wonder)?

People only thought it

Heavy thunder.

Did he have the nightmare,

Knock-a-knock!

Everybody grimly muttered:

"Earthquake shock!"

One of these tremendous fellows,

I suppose,

Could have hung your father

On his nose.

Half a score like you, sir,

(Don't look pale!)

Might have straddled see-saw

His thumb-nail.

He'd have been a crony

Worth the knowing!

For they were the kindest

Creatures going.

So good-natured, somehow,

In their ways;

Not a bit like naughty giants

Now-a-days.

Well, the biggest one among 'em,

So they tell me,

Had a pretty daughter —

Milmy-Melmy;

Ten years old precisely —

To a T;

Stout enough to make a meal of

You and me.

On her birthday, Milmy-Melmy,

All alone,

Started on a ramble —

Unbeknown.

Left her toys behind her

For a run; —

Big as elephants and camels,

Every one.

Through the country, hill and valley,

Went she fast;

Willows bent to watch her

As she passed;

Hemlock slender, poplar

Straight and high,

Brushed their tops against her fingers,

Tripping by.

Half a mile to every minute —

Like enough,

Though she found the going

Rather rough;

Men folk, glancing at her,

Cried aloud:

"We shall have a shower shortly —

See the cloud!"

Milmy-Melmy thought it rather

Jolly play

Nurse to leave behind, and

Run away;

In her life (imagine

If you can)

She had never seen a woman,

Or a man.

Three times thirty leagues of trudging

(Listen now)

Brought her to a plowman

At his plow;

Getting rather tired,

Stubbed her toe;

Stooped to see what sort of pebble

Hurt her so.

Picking up the plow and plowman,

Oxen, too,

Milmy-Melmy stared at

Something new!

Stuck them in her girdle,

Clapped her hands

Till the mountain echoes answered

Through the lands.

"Here's a better birthday present,"

Shouted she,

"Than the leather dollies

Made for me.

These are living playthings —

Very queer;

La! the cunning little carriage —

What a dear!"

So into her apron, tying

The new toy,

Off she hurried homeward

Full of joy;

Stood it on a table

In the hall;

Ran to bring her father to it,

Told him all.

"Milmy-Melmy," cried the giant,

"What a shame!

You must take the plaything

Whence it came.

These are useful workers,

Daughter mine,

Getting food for human beings, —

Corn and wine.

"Never meddle with such tiny

Folks again;

Only ugly giants love to

Trouble men."

Milmy-Melmy pouted

('T was n't nice),

But she carried back the playthings

In a trice.

When she 'd made her second journey,

Little sinner

Really felt too tired

For her dinner

So to bed they put her,

Right away,

And she had her birthday pudding

The next day.

What the plowman did about it,

Mercy knows!

Must have thought it funny,

I suppose.

If you want a moral,

Ask a fly

What he thinks of giants such as

You and I!

—St. Nicholas, June 1875, pp. 457-458.

Note: Each second line should be indented approximately 2 em spaces. Left quote marks were hanging outside the left margin.

Monday, May 12, 2008

The Hill of Gold

1895

The ragged rail fence just loafed along,

In a leisurely, zigzag line,

Down the side of the hill and wandered out

To the murmuring slopes of pine.

And I had only to climb the fence,

Or go through a crumbling gap,

To let gold spill down out of my arms

And overflow from my lap.

And the fence never cared a single bit,

For all it was there to guard,

And I might have doubled my golden spoils

Untroubled of watch or ward.

A careless old fence, and yet the hill

Broke splendidly on the eyes —

Gold clear out to the west, my dear,

And gold clear up to the skies!

And you needn't say, "Oh, it's a fairy tale!"

With that odd little scornful nod,

For it happens to be our own East hill

Grown over with goldenrod.

— Fanny Kemble Johnson.

The ragged rail fence just loafed along,

In a leisurely, zigzag line,

Down the side of the hill and wandered out

To the murmuring slopes of pine.

And I had only to climb the fence,

Or go through a crumbling gap,

To let gold spill down out of my arms

And overflow from my lap.

And the fence never cared a single bit,

For all it was there to guard,

And I might have doubled my golden spoils

Untroubled of watch or ward.

A careless old fence, and yet the hill

Broke splendidly on the eyes —

Gold clear out to the west, my dear,

And gold clear up to the skies!

And you needn't say, "Oh, it's a fairy tale!"

With that odd little scornful nod,

For it happens to be our own East hill

Grown over with goldenrod.

— Fanny Kemble Johnson.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)